[latexpage]

Electrical Shock

Electricity powers our homes, workplaces, and devices, but it carries serious risks if mishandled. Electrical shocks can cause severe injuries, burns, or even fatalities. Whether you’re a homeowner, DIY enthusiast, or professional working near electrical systems, knowing how to prevent electrical shock is essential for safety. This guide provides actionable electrical safety tips to help you avoid electric shock and prevent electrical hazards. Backed by expert insights and authoritative sources, it covers causes, prevention methods, and best practices for various settings.

By adopting these tips, you’ll create a safer environment at home or work, use the right tools, and minimize risks. Let’s dive into practical ways to stay safe from electrical hazards.

Quantitative Safety: Body Current Formulas and Lethal Thresholds

The severity of an electrical shock is governed by the current ($I$) flowing through the body, defined by the voltage ($V$) and the body’s electrical resistance ($R_{body}$) via Ohm’s Law:

$$I = \frac{V}{R_{body}}$$

Human body resistance ($R_{body}$) varies greatly: dry skin can offer over $100 \text{k}\Omega$, while wet skin or compromised tissue can drop resistance below $1 \text{k}\Omega$.

Key Electrical Thresholds (IEC 60479)

- Threshold of Perception: Approximately $1 \text{ mA}$. The point where current is first felt.

- Let-Go Threshold: Approximately $10 – 16 \text{ mA}$. Maximum current at which a person can still control their muscles to release the conductor.

- Ventricular Fibrillation / Lethal Threshold: Currents above $50 \text{ mA}$ flowing across the chest are highly likely to be fatal.

Safe Touch Voltage Limit

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC 60479) sets the maximum Safe Touch Voltage limits for AC current at $\le 50 \text{V}$.

Danger Example: A standard $230 \text{V}$ line across wet skin ($R_{body} \approx 1000 \Omega$) results in a current of $I = 230 \text{V} / 1000 \Omega = 0.23 \text{A}$ or $230 \text{mA}$. This is over four times the lethal threshold.

Understanding Electrical Shock: What You Need to Know

An electrical shock occurs when a person’s body completes an electric circuit, allowing current to flow through it. This can happen via contact with live wires, faulty appliances, or conductive surfaces like water. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), electrical incidents cause hundreds of workplace injuries annually, many preventable with proper precautions. Shocks vary in severity based on current strength, duration, and path through the body, ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening conditions like cardiac arrest.

Homeowners often face shocks from damaged cords or improper appliance use, while workers in construction or maintenance encounter risks from exposed wires or power lines. Recognizing these dangers is the first step to effective electrical hazard prevention.

Common Causes of Electrical Shock

To avoid electric shock, you must identify its common triggers. Here are the primary causes:

- Contact with Live Wires: Accidental contact during construction or DIY projects can lead to shocks.

- Faulty or Damaged Equipment: Frayed cords, cracked insulation, or malfunctioning appliances increase risks.

- Water and Electricity: Wet hands or environments near electrical devices amplify conductivity.

- Improper Grounding: Lack of proper grounding can energize metal parts, causing shocks.

- Overhead Power Lines: Working too close without precautions poses severe risks.

Understanding these hazards helps you take targeted steps to prevent electrical shock in various settings.

Case Studies and Technical Applications of Prevention Methods

Household Safety: GFCI Protection (NEC 210.8)

- Method: Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) outlet.

- Technical Operation: A GFCI constantly monitors the current balance between the hot and neutral wires. If the imbalance (leakage current) exceeds $5 \text{ mA}$ ($0.005 \text{A}$) for $\le 25 \text{ milliseconds}$, the device trips the circuit. This speed is critical to preventing the current from reaching the $50 \text{ mA}$ threshold that causes heart fibrillation.

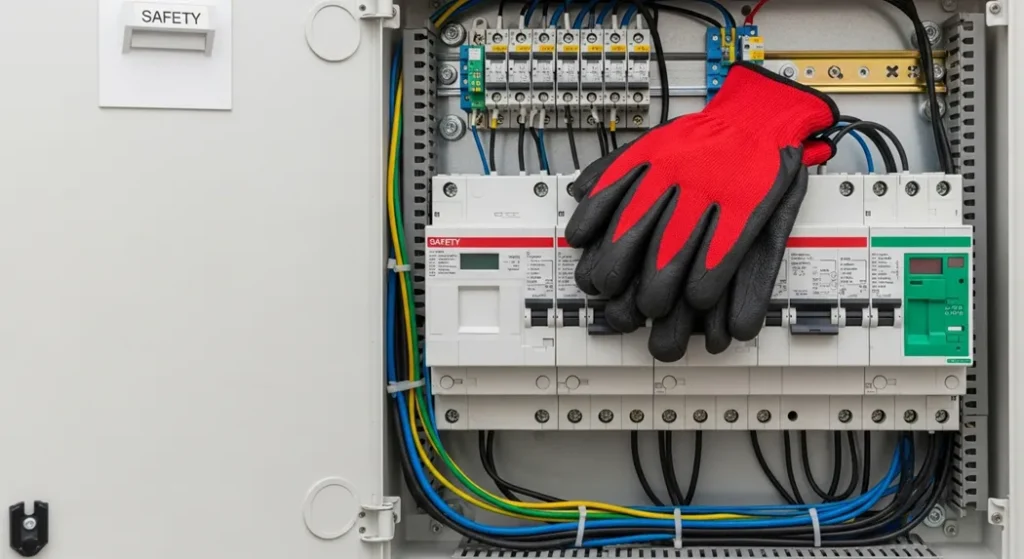

Industrial Safety: Insulated Tools and PPE

- Method: Use of Dielectric (Insulating) Gloves.

- Standard: Gloves must meet ASTM D120 classifications. Class 1 gloves, for instance, are tested at $10 \text{kV}$ and rated for use up to $7.5 \text{kV}$. This ensures a massive resistance barrier (megohms) between the worker and the conductor, maintaining $R_{body}$ artificially high and keeping $I$ near zero.

Accident Analysis: Faulty Grounding

- Scenario: A piece of metal-cased equipment has damaged internal insulation, causing the hot wire to touch the metal casing. If the grounding wire is faulty or missing, the casing becomes energized.

- Result: When a worker touches the casing, their body becomes the only path to ground. This is a severe shock hazard that proper equipment grounding (as defined by IEEE Std 80) and functional GFCIs are designed to prevent.

Comparison Table: Electrical Protection Methods

| Protection Method | Trip/Safety Threshold | Typical Use | Primary Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFCI (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter) | $5 \text{ mA}$ Trip Current | Residential Wet Locations (Bathrooms, Kitchens) | NEC 210.8 (UL 943) |

| RCD (Residual Current Device) | $30 \text{ mA}$ (Common Industrial/European Standard) | Industrial Circuits, General Wiring | IEC 61008 / IEC 61009 |

| Insulation (Cables/Tools) | $> 1 \text{ M}\Omega$ Resistance (prevents current flow) | Wiring, High-Voltage Tools | IEC 60216 / ASTM D120 |

| Grounding/Earthing | Low Resistance Path to Earth (Zeroing potential) | Substations, Power Distribution Systems | IEEE Std 80 |

Electrical Safety Tips for Homeowners

Homeowners can reduce electrical shock risks with practical safety measures. Here’s how to protect your household:

Inspect Cords and Appliances Regularly

Check power cords, plugs, power supply and outlets for fraying, exposed wires, or loose connections. Replace damaged items immediately to prevent shocks or fires, as advised by the Electrical Safety Foundation International (ESFI). Never use appliances with visible damage, and avoid DIY repairs unless qualified.

Use Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCIs)

GFCIs detect imbalances in electrical current and shut off power to prevent shocks. Install them in wet areas like kitchens, bathrooms, and outdoor spaces, as recommended by Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). Test GFCIs monthly to ensure they function properly.

Avoid Water Near Electrical Devices

Never operate electrical appliances with wet hands or near water sources. Keep devices like hairdryers or chargers away from sinks and bathtubs to avoid electric shock.

Use Proper Wattage for Light Bulbs

Using bulbs with higher wattage than a fixture’s rating can cause overheating, leading to shocks or fires. Follow manufacturer recommendations, as noted by Energy Star guidelines.

Install Tamper-Resistant Receptacles

For homes with young children, tamper-resistant receptacles prevent objects from being inserted into outlets, reducing shock risks, as outlined by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Electrical Safety Tips for Workers

Workers in construction, maintenance, or electrical trades face elevated risks. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that construction accounts for a significant portion of electrical fatalities, often due to contact with power lines or tools. Here’s how to stay safe on the job:

De-Energize Equipment Before Work

Always turn off and lock out power sources before inspecting or repairing electrical equipment. Use lockout/tagout procedures to ensure circuits remain de-energized, per OSHA’s lockout/tagout standards.

Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Wear rubber-insulated gloves, non-conductive helmets, and safety goggles when working near live parts. Ensure PPE is tested and maintained according to Underwriters Laboratories (UL).

Maintain Safe Distances from Power Lines

Stay at least 10 feet away from overhead power lines. Use non-conductive ladders and tools to minimize risks, as advised by the International Association of Electrical Inspectors (IAEI).

Use Insulated Tools

Choose tools with insulated handles designed for the voltages you’re working with. Inspect tools for damage before use and remove defective ones from service.

Undergo Electrical Safety Training

Regular training helps workers recognize hazards and follow safe practices, as recommended by NFPA 70E standards. Training reduces workplace accidents significantly.

Troubleshooting Common Electrical Safety Symptoms

Understanding the symptom of an electrical fault is the first step in prevention and repair.

Symptom: Tingling or “Buzz” When Touching Metal Appliance Casing

- Cause: Leakage Current (often $1 \text{ mA}$ to $5 \text{ mA}$) due to damaged internal wiring or wet conditions, causing the metal chassis to float at a low potential relative to ground.

- Fix: Immediately remove the appliance from service. Check insulation integrity. Install a GFCI outlet, which will trip if the leakage exceeds $5 \text{ mA}$.

Symptom: Breaker/GFCI Trips Frequently

- Cause: Persistent Ground Fault. A permanent fault path to ground is occurring, possibly due to worn-out appliance cords or moisture ingress in the wiring system.

- Fix: Isolate the problem circuit by unplugging all devices, resetting the breaker, and plugging devices back in one by one until the circuit trips again. Inspect the wiring for signs of damage or heat.

Symptom: Visible Exposed Wires or Burn Marks

- Cause: Damaged Insulation due to physical stress (pinching), age (brittleness), or overheating.

- Fix: Never attempt temporary fixes like electrical tape on high-voltage wires. The cable must be professionally replaced or the section of damaged insulation must be repaired using UL-rated methods and heat-shrink tubing.

Safety Tools and Equipment for Electrical Hazard Prevention

Using the right tools is critical for avoiding electric shock. Here are key tools to incorporate:

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCIs)

GFCIs are essential for cutting power during a fault. They’re mandatory in high-risk areas like construction sites and wet environments, as per Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Insulating Mats and Blankets

Rubber insulating mats provide a non-conductive barrier for workers handling live equipment, vital in industrial settings, as outlined by IEEE standards.

Voltage Testers

Use an AC voltage tester to verify circuits are de-energized before starting work. This ensures no live current is present, a practice endorsed by ESFI.

Arc-Flash Protective Gear

For high-voltage work, arc-rated flame-resistant clothing protects against burns and shocks caused by arc flashes. Follow NFPA 70E guidelines for selection.

Visual Recommendation: Create an infographic showing essential safety gear (e.g., GFCIs, insulating gloves, voltage testers) with alt text: “Infographic of electrical safety tools including GFCI outlets, rubber gloves, and voltage testers for preventing electrical shock.”

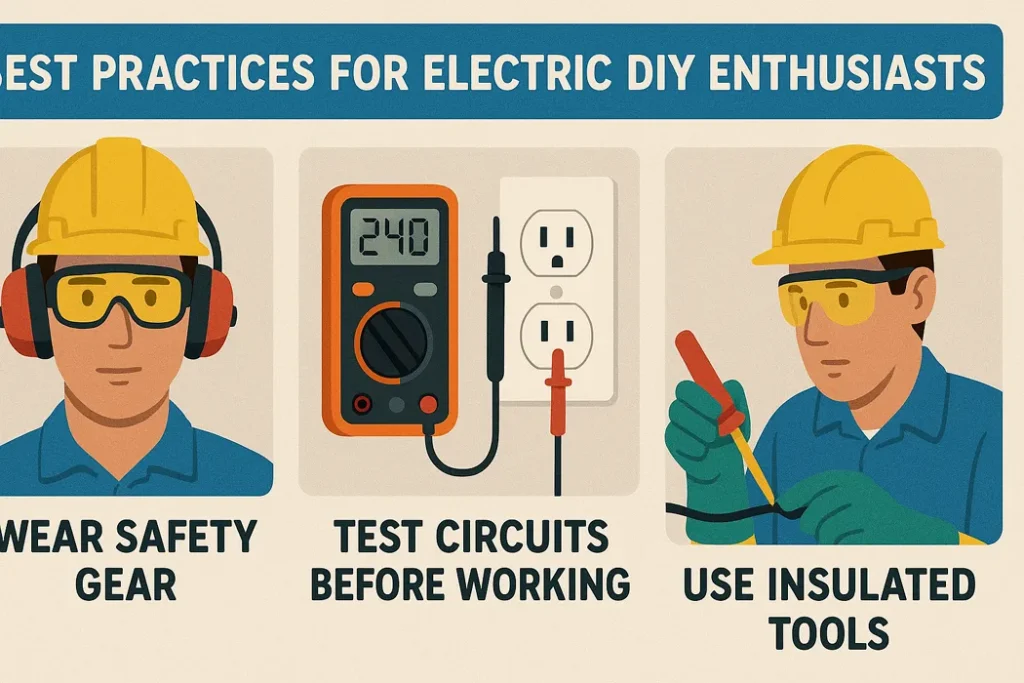

Best Practices for DIY Enthusiasts

DIY electrical projects can be rewarding but risky. Follow these best practices to avoid electric shock:

Turn Off Power at the Breaker

Before starting any electrical work, switch off the circuit at the main breaker and use a voltage tester to confirm it’s off. Never assume a circuit is de-energized, as warned by Hydro-Québec’s safety tips.

Avoid Overloading Outlets

Plugging multiple devices into a single outlet can cause overheating. Use surge protectors or power strips with built-in circuit breakers, as recommended by CPSC.

Hire a Professional for Complex Tasks

If you’re unsure about your skills, hire a licensed electrician. DIY mistakes can lead to shocks, fires, or code violations, per ESFI.

Use Extension Cords Wisely

Choose heavy-duty extension cords rated for your project, and never use indoor cords outdoors. Avoid daisy-chaining cords, which increases shock risks.

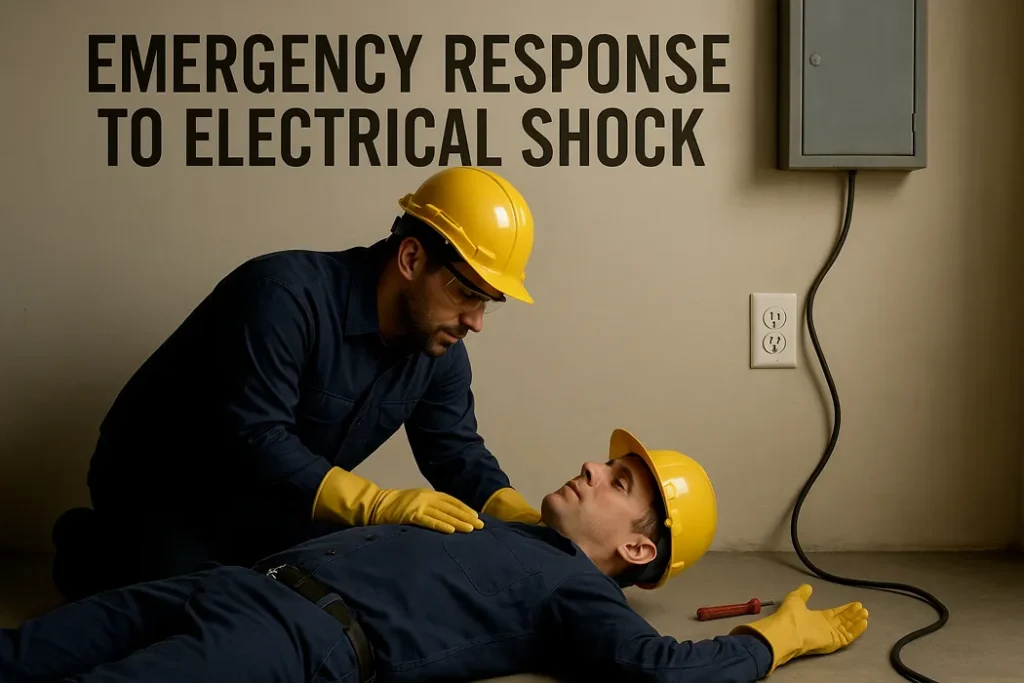

Emergency Response to Electrical Shock

Despite precautions, accidents can happen. Here’s how to respond, based on American Red Cross guidelines:

- Turn Off the Power: If someone is being shocked, immediately shut off the power source if safe to do so.

- Avoid Direct Contact: Use a non-conductive object, like a wooden stick, to separate the victim from the source. Do not touch them directly.

- Check for Vitals: If the victim is unresponsive, check for breathing and pulse. Begin CPR if necessary and call emergency services.

- Seek Medical Attention: Even minor shocks require medical evaluation, as internal injuries may not be immediately visible.

Creating a Culture of Electrical Safety

Preventing electrical shock requires a proactive safety culture. Employers should conduct regular safety drills, reward safe behavior, and ensure staff are trained, as recommended by OSHA. Homeowners should educate family members, especially children, about electrical hazards. Clear signage for high-voltage areas and routine inspections by qualified electricians further reduce risks, as noted by National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA).

Industry Standards and Compliance

Compliance with these key standards ensures maximum electrical safety, from power generation to residential outlets.

Safety and Design Codes

- NEC (NFPA 70): The National Electrical Code is the foundation for safe electrical installation in the US, mandating where protection devices like GFCIs must be installed (Section 210.8).

- OSHA 29 CFR 1910: US federal regulations governing Workplace Electrical Safety. This code mandates specific procedural standards, most notably Lockout/Tagout (LOTO) procedures (29 CFR 1910.147).

- IEC 60479 (Effects on Humans): International standard providing the technical data on the effects of current passage through the human body and defining the Safe Touch Voltage limits.

Grounding and Testing Standards

- IEEE Std 80: A highly specialized standard outlining the safety requirements for AC Substation Grounding. It details how to calculate and design grounding systems to minimize step and touch voltages in high-power environments.

- UL 943: The Underwriters Laboratories standard that dictates the construction, testing, and performance requirements for all Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCIs).

Conclusion: Stay Safe with Proactive Measures

Preventing electrical shock requires awareness, preparation, and action. By understanding risks, using tools like GFCIs and insulated gear, and following safety practices, you can protect yourself and others. Whether you’re a homeowner inspecting cords, a worker near power lines, or a DIYer tackling a project, these electrical safety tips can save lives. Stay vigilant, prioritize training, and consult professionals when needed.

Call to Action: Have you implemented these safety tips? Share your experiences or additional advice in the comments below!

FAQ: Common Questions About Electrical Shock Prevention

What is the safe touch voltage for humans?

“Safe” touch voltage varies by standard and environment, but generally anything below 50 V AC (or 120 V DC ripple-free) is considered a non-hazardous touch voltage under normal dry conditions.

Standards such as IEC 60479 define that voltages under 50 V AC are unlikely to cause dangerous shock currents under most conditions.

Wet conditions significantly lower the safe threshold (as low as 12–25 V).

How does a GFCI prevent electrical shock?

Ground-Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) constantly compares the current flowing out through the hot conductor with the current returning through the neutral.

If there is even a 4–6 mA difference, indicating current flowing through a person or to ground, the device trips within milliseconds, cutting off power and preventing severe shock.

Which standards govern electrical safety?

Common electrical-safety standards include:

- NFPA 70 – National Electrical Code (NEC)

- NFPA 70E – Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace

- OSHA 29 CFR 1910 Subpart S & 1926 Subpart K

- IEC 60364 – Low-voltage electrical installations

- IEC 60479 – Effects of Current on the Human Body

- UL / CSA standards for testing and certification

What causes electrical shocks?

Shocks occur when a person contacts a live electrical source, completing a circuit. Common causes include damaged cords, wet conditions, and improper grounding, per ESFI.

How can I make my home safer from electrical shocks?

Install GFCIs, use tamper-resistant outlets, inspect cords regularly, and avoid using electrical devices near water, as advised by CPSC.

What PPE is needed for electrical work?

Rubber gloves, non-conductive helmets, and arc-rated clothing are essential, depending on the task. Follow NFPA 70E and UL guidelines.

Can low-voltage shocks be dangerous?

Yes, even low-voltage shocks can cause injury, especially with prolonged exposure. Always treat electricity with caution, as noted by NIOSH.

Author Bio:

Author is a licensed electrician with over 15 years of experience in residential and commercial electrical systems. Certified in NFPA 70E safety standards, he specializes in promoting workplace and home safety.