Squirrel cage induction motors have earned a reputation as the backbone of industrial motion. Engineers rely on them for everything from pumps and compressors to conveyors, blowers, HVAC equipment, and general machinery. Their popularity is not accidental. These motors combine rugged construction, high efficiency, long-term durability, and intuitive operating behavior in a way few electrical machines can match.

This tutorial is written from a professional engineering perspective. By the end, you will understand the motor’s construction, operating principle, torque–speed behavior, NEMA design types, typical applications, advantages, limitations, and how modern VFDs and starters integrate with it. The goal is to explain the motor clearly enough that a junior engineer could design, select, or troubleshoot one with confidence.

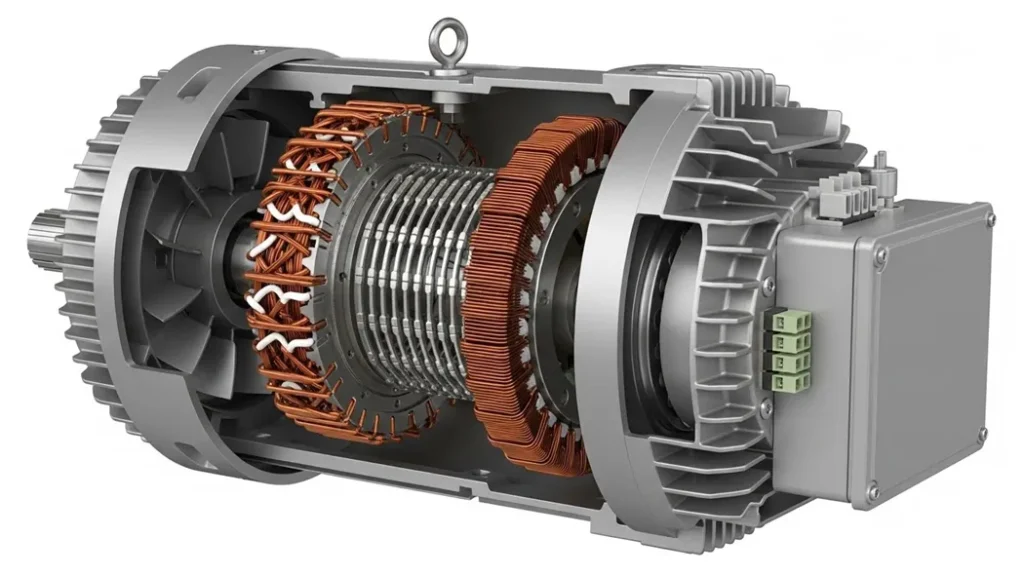

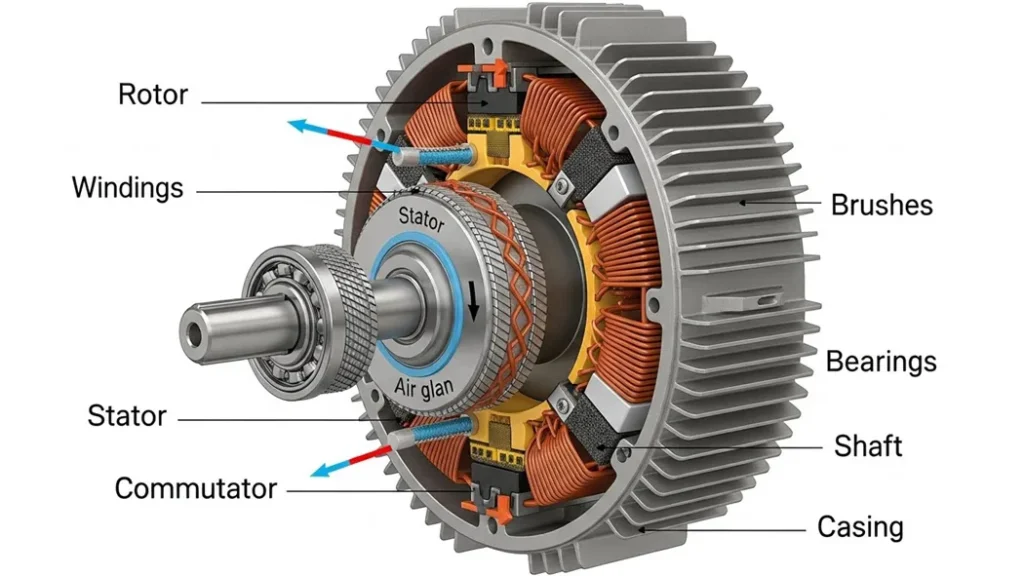

Understanding the Motor’s Physical Construction

Any induction motor, no matter the rating or manufacturer, is built around two major components: the stator and the rotor. The stator forms the stationary outer shell. Inside it are stacked thin laminations of high-grade electrical steel. These laminations contain slots that hold the three-phase windings. When AC flows through these windings, they produce a rotating magnetic field. The design and insulation of these windings determine how well the motor can tolerate heat, voltage imbalance, thermal cycling, and harmonics. Modern motors typically use Class F or Class H insulation systems, which can withstand significantly higher temperatures and thereby extend service life.

Advanced Construction Details: Skewing and Materials

The reliability of the squirrel cage motor stems from subtle design decisions that mitigate common issues.

The Purpose of Rotor Bar Skewing

The rotor bars are intentionally built with a slight twist (skew) along the rotor’s axis. This is done for two primary engineering reasons:

- Eliminate Magnetic Locking (Cogging): Skewing ensures the rotor teeth never perfectly align with the stator teeth, preventing a momentary lock-up that would make the motor difficult or impossible to start.

- Reduce Noise and Torque Ripple: The continuous variation in the magnetic path smooths out the torque production, significantly reducing the operational noise (acoustic output) and vibration.

Rotor Material Selection

While often called the “Squirrel Cage,” the material is crucial:

- Cast Aluminum: Most common for general-purpose motors (NEMA Design B). It is cheap, easy to manufacture (die-casting), and offers a good balance of resistance and cost.

- Copper/Copper Alloys: Used in high-efficiency motors (IE3/IE4). Copper has lower resistance than aluminum, which reduces $I^2R$ losses, improving efficiency but increasing manufacturing cost.

Understanding motor working in a squirrel cage induction motor boils down to Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. Here’s how it unfolds:

- Stator Energization: A three phase electric motor supply (typically 3-phase AC at 50/60 Hz) feeds the stator windings, creating a rotating magnetic field (RMF) at synchronous speed (Ns = 120f/P, where f is frequency and P is poles).

- Induction in Rotor: The RMF “cuts” the induction rotor bars, inducing EMF and current via electromagnetic induction motor principles. This produces a secondary magnetic field in the rotor.

- Torque Generation: The rotor field interacts with the stator RMF, causing the rotor to “chase” the field. Due to slip (2-5% in loaded conditions), the rotor lags slightly, maintaining torque. No slip ring needed—currents loop through the cage.

- Steady-State Operation: The rotor reaches ~95-98% of Ns, with motor control via VFDs (Variable Frequency Drives) for speed adjustments.

For AC AC motor visuals, imagine the squirrel cage bars as a short-circuited transformer secondary pure induction magic!

Equation Spotlight: Slip (s) = (Ns – Nr)/Ns, where Nr is rotor speed. For a 4-pole, 60 Hz AC motor, Ns = 1800 RPM; typical Nr = 1750 RPM (s=0.0277).

Deeper Mathematical Model and Performance Analysis

To fully understand motor behavior, particularly under load, engineers rely on the full torque-slip relationship and power factor calculations.

Torque as a Function of Slip (T-s Relationship)

The torque ($T$) developed by an induction motor is dependent on the parameters of the equivalent circuit and the slip ($s$). While complex, the key relationship in the operating region is:

$$T \propto \frac{s \cdot E_2^2 \cdot R_2}{R_2^2 + (s \cdot X_2)^2}$$

Where:

- $E_2$: Induced EMF in the rotor at standstill.

- $R_2$: Rotor resistance per phase.

- $X_2$: Rotor reactance per phase at standstill.

- $s$: Slip.

This formula demonstrates that maximum (breakdown) torque occurs when the rotor reactance equals the rotor resistance, $R_2 = s \cdot X_2$.

Efficiency and Industry Standards (IE Classes)

Modern industrial motors are strictly governed by efficiency standards. In the international market, the IEC 60034-30 standard defines mandatory **International Efficiency (IE) classes**. Engineers must select motors based on their IE rating to comply with energy regulations:

- IE1: Standard Efficiency

- IE2: High Efficiency

- IE3: Premium Efficiency (Most common new installations)

- IE4: Super Premium Efficiency

Achieving a higher IE rating primarily involves reducing rotor copper losses ($P_{cu}$), which is directly proportional to slip ($P_{cu} = s \cdot P_{g}$, where $P_g$ is the air-gap power). This often means using more expensive, low-resistance materials like copper for the rotor bars instead of cast aluminum.

Inside the stator’s rotating magnetic field sits the rotor. This rotor is what gives the squirrel cage motor its name. It consists of steel laminations with conductive bars embedded along their length. These bars are usually cast aluminum or copper and are permanently short-circuited by end rings. When viewed from the side, the structure resembles the exercise wheel of a small animal, which led to the name “squirrel cage.” Importantly, the rotor bars are not perfectly straight. They are skewed slightly to reduce magnetic locking and lower torque ripple and noise.

The rotor is mounted on a shaft supported by bearings at both ends. Most industrial designs use deep-groove ball bearings or roller bearings depending on the radial and axial loads. A fan is attached to the shaft, forcing air across the frame as the motor runs. The external frame is shaped with cooling fins to improve heat dissipation. This combination of aerodynamic cooling, heat-tolerant insulation, and simple mechanical design contributes to the motor’s reputation for long-term reliability.

Key types include:

- Induction motors: Rely on electromagnetic induction motor for rotor excitation without direct connections.

- Synchronous motors: Lock to the supply frequency for precise speed control.

How the Motor Works: Electromagnetic Induction in Motion

The operating principle is rooted in Faraday’s Law and Lenz’s Law. When three-phase AC is applied to the stator windings, it generates a rotating magnetic field that travels around the stator’s inner surface. The speed of this rotating field, called synchronous speed, depends on the supply frequency and the number of stator poles.

The operating principle is rooted in Faraday’s Law and Lenz’s Law. When three-phase AC is applied to the stator windings, it generates a rotating magnetic field that travels around the stator’s inner surface. The speed of this rotating field, called synchronous speed, depends on the supply frequency and the number of stator poles.

The formula for synchronous speed is: Ns=120fPN_s = \frac{120f}{P}

When the stator’s rotating field sweeps across the rotor bars, it induces an electromotive force because the magnetic field experienced by the rotor is constantly changing. Since the rotor bars are short-circuited, current flows within them. This current produces its own magnetic field. The interaction between the stator’s rotating field and the rotor’s induced magnetic field generates torque.

A key concept here is slip the difference between the synchronous speed of the rotating field and the actual rotor speed. Slip is not a defect. It is the fundamental mechanism that allows torque to exist. Without slip, there would be no relative motion between the magnetic field and the rotor, and no current would be induced.

Slip is expressed as: s=Ns−NrNss = \frac{N_s – N_r}{N_s}

In practice, slip decreases as the motor reaches steady-state speed. A lightly loaded motor may operate with only 1–3% slip, while a heavily loaded motor may show slightly higher values. The self-regulating nature of slip is what allows the motor to adapt naturally to load variations without complex control systems.

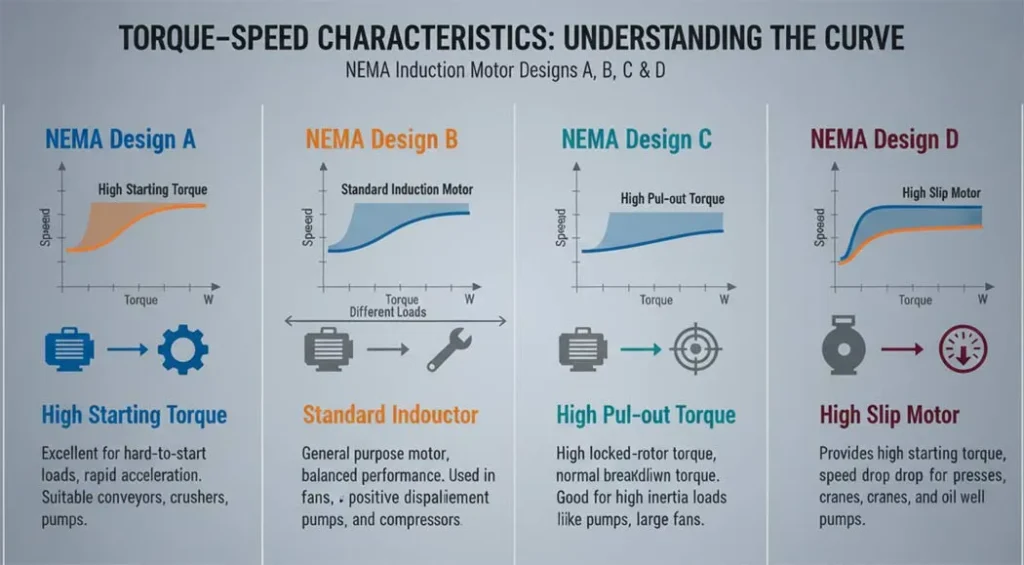

Types of Squirrel Cage Induction Motors: NEMA Classifications

Squirrel cage motors aren’t one-size-fits-all. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) classifies them into designs for tailored performance:

| Design Class | Starting Current | Starting Torque | Efficiency | Slip | Ideal Applications |

| Class A | High (5-8x FL) | Medium | High | Low (1-2%) | Motor small tools, fans, pumps classic AC motor workhorses. |

| Class B | Medium (3-5x FL) | Medium | High | Low | General 3 phase electric motor drives; replaces Class A in modern motor control. |

| Class C (Double Cage) | Low (2-3x FL) | High | Medium | Medium | Motors for air compressors, conveyors boosts motor starting torque. |

| Class D (High Resistance) | Low (1-2x FL) | Very High | Low | High (5-13%) | Punch presses, hoists handles high-inertia loads. |

| Class E | Normal | Low | High | Very Low | Precision induction machine apps like textiles. |

| Class F | Low | Low | High | Normal | Low-torque, high-efficiency AC AC motor setups. |

Squirrel Cage vs. Slip Ring Induction Motors: A Head-to-Head Comparison

| Feature | Squirrel Cage Induction Motor | Slip Ring Induction Motor |

| Construction | Simple, brushless squirrel cage—no slip ring. | Complex with slip ring, brushes, resistors. |

| Maintenance | Low; rugged for motor electric motor reliability. | High; brushes wear out. |

| Starting Torque | Medium (Class B/C enhanced via motor starter). | High, adjustable via external resistance. |

| Efficiency | High; minimal copper losses in induction rotor. | Lower due to brush friction. |

| Speed Control | Limited; use VFD for motor control. | Excellent with rotor resistors. |

| Cost | Affordable for three phase electric motor bulk buys. | Higher upfront. |

| Safety | Explosion-proof; pairs with circuit breaker types. | Similar, but brushes add spark risk. |

Torque–Speed Characteristics: Understanding the Curve Professionally

Every induction motor follows a predictable torque speed relationship. At standstill, slip is 100%, and the rotor sees the maximum possible relative motion. As the motor begins to turn, torque rises. Eventually the motor reaches what is known as breakdown torque the maximum torque the motor can produce without losing stability. Beyond this point, the torque declines. In normal operation, the motor works well below breakdown torque, in the low-slip region where torque changes smoothly with small changes in load. This inherent stability is one of the reasons these motors are considered nearly foolproof for industrial duty. A useful mental model is to imagine the rotor constantly “chasing” the stator’s rotating field. It never catches it, but the small lag creates the torque required to drive mechanical loads.

Every induction motor follows a predictable torque speed relationship. At standstill, slip is 100%, and the rotor sees the maximum possible relative motion. As the motor begins to turn, torque rises. Eventually the motor reaches what is known as breakdown torque the maximum torque the motor can produce without losing stability. Beyond this point, the torque declines. In normal operation, the motor works well below breakdown torque, in the low-slip region where torque changes smoothly with small changes in load. This inherent stability is one of the reasons these motors are considered nearly foolproof for industrial duty. A useful mental model is to imagine the rotor constantly “chasing” the stator’s rotating field. It never catches it, but the small lag creates the torque required to drive mechanical loads.

NEMA Design Types: How Motors Behave Under Different Loads

Industrial loads vary widely. A pump impeller accelerates smoothly. A conveyor may start under partial load. A compressor may demand aggressive torque right from startup. To address these differences, NEMA design classes were introduced. Each class defines the motor’s starting torque, starting current, running characteristics, and slip behavior.

A Design B motor is the most common option today and provides low-slip operation suited for general-purpose applications like HVAC fans, blowers, and centrifugal pumps. Design A motors behave similarly but may draw higher starting currents. Design C motors are engineered for demanding starts, such as air compressors and heavily loaded conveyors. Their rotors often use a double-cage structure to increase starting torque. Design D motors occupy a niche where extraordinarily high starting torque is required, such as in hoists and punch presses, though they operate with higher slip and lower efficiency.

Understanding these classes helps engineers avoid common selection mistakes. For example, installing a Design B motor on a high-inertia mixer often results in overheating and premature failure. Switching to a Design C motor solves the issue instantly.

Where Squirrel Cage Motors Are Used

Where Squirrel Cage Motors Are Used

Squirrel cage motors remain the first choice for systems requiring dependable, continuous rotation. Industrial air compressors depend on them for their ability to deliver high startup torque and handle cyclical loading. Pump systems rely on them because they tolerate moisture, misalignment, and constant duty. HVAC systems whether rooftop units, chillers, or large building blowers trust these motors because they run quietly and efficiently for thousands of hours.

Material handling equipment such as conveyors depends on the motor’s natural torque–slip behavior. As the load increases, the motor compensates automatically without requiring sensors or digital controls. CNC machines and precision equipment benefit from the motor’s stable, low-vibration operation. Food mixers, crushers, grinders, and other variable-load machines use these motors because they withstand unpredictable torque spikes. For nearly every rotating application where simplicity and durability matter, the squirrel cage motor remains the undisputed favorite.

Engineering Case Studies and Quantitative Analysis

A true professional resource must move beyond theory and demonstrate how the formulas and standards are used to make critical design decisions.

Case Study 1: Motor Selection for High-Inertia Load (Conveyor System)

Consider a conveyor belt starting under a high static load. A general-purpose NEMA Design B motor might take 10 seconds to reach full speed, causing excessive heat and wear. An engineer would use the following approach:

- Problem: Initial current draw is too high, leading to system voltage sag.

- Solution: The engineer selects a NEMA Design C motor. While its efficiency might be slightly lower, its higher **Starting Torque** (typically 200–250% of full load torque) allows the motor to clear the high inertia and reach steady state in under 5 seconds, dramatically reducing the thermal stress on the windings and the inrush current duration.

- Takeaway: Selecting a motor for high starting torque (Design C/D) often outweighs the need for peak running efficiency (Design B) when the starting cycle is demanding.

Case Study 2: Quantifying the Risk of Voltage Unbalance

The danger of running a motor with unbalanced voltage can be quantified using the NEMA derating factors (MG 1-14.35). While $V_{Unbal}$ seems small, the effect on motor heating is exponential.

- A **1% voltage unbalance** in the supply can lead to a **6% to 10% increase** in the motor’s **temperature rise**.

- A **5% voltage unbalance** (a large but possible fault) can cause the motor to run up to **30% hotter** than its design temperature.

Practical Check: If a motor is rated Class F insulation (max rise $105^{\circ}C$), even a small unbalance can push it into a critical zone, halving the expected insulation life. This demonstrates that continuous monitoring of line voltage is a crucial preventative maintenance step, not just a theoretical concern.

Strengths of the Squirrel Cage Induction Motor

From an engineering perspective, the greatest strength of this motor is mechanical simplicity. A rotor with no electrical connections, brushes, or slip rings means fewer components can fail. The stator windings, if properly protected from overheating, can last decades. The motor’s high efficiency translates into operational savings, particularly in plants with dozens or hundreds of motors. Another major advantage is the motor’s tolerance for environmental stress. Dust, vibration, fluctuating temperatures, and moderate voltage variations rarely affect its operation.

With proper cooling and maintenance, these motors run continuously for months at a time. Their compatibility with modern VFDs significantly increases their versatility. Instead of operating at fixed speed, motors can now vary speed smoothly, reduce energy consumption, and start without the heavy inrush currents that once strained electrical systems.

Advantages of Squirrel Cage Induction Motors: Why They’re Industry Favorites

- Rugged Simplicity: No slip ring means fewer failures in harsh motor working environments.

- High Efficiency: Up to 95% in 3 phase motors, slashing energy bills.

- Low Cost & Maintenance: Ideal for motor small to industrial scales.

- Overload Tolerance: Handles surges with electric breaker backups.

- Constant Speed: Perfect for motors for air compressors and fans.

In 2025, with rising energy regs, these AC AC motor gems lead in green manufacturing.

Limitations and How Engineers Manage Them

Although robust, these motors do have limitations. The biggest challenge is the high starting current when connected directly to the supply. In large motors, this can cause voltage dips across an electrical system. Engineers mitigate this by using star–delta starters, autotransformer starters, or soft starters. Without a VFD, the motor’s speed cannot be altered significantly. This was once a major limitation, but modern drives have made variable-speed operation routine.

Voltage imbalance is another concern. Even a small imbalance can cause disproportionately large increases in rotor heating. This reduces insulation life if left uncorrected. Cooling path obstructions, poor alignment, and overloading are other common issues, but these relate more to maintenance practices than to the motor’s inherent design.

Disadvantages and Mitigation Strategies

No motor is perfect here’s the flip side:

- High Starting Current: 5-7x full load; mitigate with motor starter like star-delta.

- Poor Speed Control: Native slip limits variability; fix via motor control inverters.

- Voltage Sensitivity: Fluctuations cause overheating; use circuit circuit breaker stabilizers.

- Low Light-Load PF: Improves under load, but add capacitors for induction motor tweaks.

For motor starting woes, soft starters are game-changers.

Motor Starters, MCCs, and Protection Systems

A proper motor installation relies heavily on the associated control and protection equipment. In motor control centers, contactors handle switching operations, overload relays protect against slow thermal overload, and circuit breakers protect against short circuits. Breakers are typically sized at 125% of the motor’s full-load current to allow for startup conditions.

A proper motor installation relies heavily on the associated control and protection equipment. In motor control centers, contactors handle switching operations, overload relays protect against slow thermal overload, and circuit breakers protect against short circuits. Breakers are typically sized at 125% of the motor’s full-load current to allow for startup conditions.

Starter selection depends on the motor’s size and load characteristics. Small motors may be started directly. Larger motors use star–delta or soft starters to reduce mechanical and electrical stress. VFDs are increasingly preferred because they offer controlled acceleration, speed regulation, torque management, and built-in protection features.

The Modern Role of VFDs in Induction Motor Systems

Variable Frequency Drives changed the way engineers design motor-driven systems. Instead of running motors continuously at full speed, VFDs allow precise speed control based on process demand. A pump in a chilled water system can reduce speed drastically during low demand periods, saving significant energy. A conveyor can adjust its speed to match production scheduling. A compressor can ramp up gently without the heavy electrical punch characteristic of direct starts.

VFDs also reduce mechanical stress, extend bearing life, improve power quality, and provide real-time monitoring. Their integration with squirrel cage motors has made variable-speed control both affordable and reliable in nearly every industrial sector.

A Realistic Engineering Workflow: How Motors Are Installed and Commissioned

A professional motor installation begins with mechanical alignment. Any misalignment between the motor shaft and the driven load increases bearing stress and leads to premature failure. After alignment, the electrical team connects the motor to the appropriate starter or VFD and verifies correct phase rotation using a brief no-load energization. The motor is then allowed to run unloaded so the technician can listen for noise, check vibration, and confirm that cooling airflow is unobstructed. Only after these confirmations is the load coupled and the system tested under actual working conditions. This carefully staged approach ensures a stable, trouble-free installation that remains reliable for years.

Real-World Applications: From Air Compressors to Beyond

Squirrel cage induction motors power the backbone of industry:

- Motors for Air Compressors: Class C designs deliver high motor starting torque for pressure builds.

- Pumps & Fans: Low-slip 3 phase electric motor ensures steady flow.

- Conveyors & Mixers: Rugged squirrel cage handles cyclic loads.

- HVAC & Refrigeration: Efficient AC motor cooling in large systems.

- CNC Machines: Paired with motor control for precision.

In EVs, hybrid induction machine variants boost regenerative braking.

Field Diagnostics and Common Fault Analysis

While robust, squirrel cage motors still fail due to common electrical or mechanical issues. A professional engineer uses specific diagnostic tests to pinpoint the problem:

Fault 1: Motor Overheating Diagnosis

Overheating is the number one cause of winding insulation failure. Diagnosis should immediately check for voltage irregularities:

| Diagnostic Step | Standard & Threshold | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Measure Voltage Unbalance | NEMA MG 1-14.35 (Should be < 1.0%) | Calculate: $$V_{Unbal} = \frac{\text{Maximum Deviation from Average}}{\text{Average}} \times 100$$ If over 1%, motor must be de-rated or source corrected. |

| Check Insulation Resistance | IEEE Standard 43 (Minimum 1 MΩ per 1 kV) | Use a Megohmmeter (Megger) to test resistance between winding and ground. Low resistance indicates moisture or insulation damage. |

Fault 2: Motor Fails to Start (Single-Phasing)

A humming, non-starting motor often indicates one phase is open. Use an ohmmeter to check the stator windings:

- Measure resistance between Phase A and B ($R_{AB}$), Phase B and C ($R_{BC}$), and Phase C and A ($R_{CA}$).

- For a healthy motor, all three readings should be **nearly identical** (within 5% tolerance).

- A reading of **infinity (OL)** on one pair indicates an open circuit, usually a blown fuse, tripped breaker, or internal winding break.

Conclusion: Why the Squirrel Cage Induction Motor Still Leads in 2025

After more than a century of engineering advances, the squirrel cage induction motor remains the industrial standard for dependable mechanical power. Its construction is simple, its performance is predictable, and its reliability is unmatched. With modern improvements better insulation, improved rotor casting, refined cooling systems, and VFD compatibility the motor is even more durable and efficient than older versions.

Whether installed in a factory, on a rooftop, in a pumping station, or inside a conveyor system, it continues to serve as the most trusted, cost-effective, and widely deployed machine for converting electrical energy into motion. The squirrel cage induction motor isn’t just an electric motor it’s a testament to elegant engineering, blending induction machine physics with practical motor control. From AC AC motor basics to advanced three phase electric motor deployments, mastering this tech elevates your industrial edge.

FAQs: Quick Answers on Squirrel Cage Induction Motors

1. What makes a squirrel cage motor different from other induction motors?

The squirrel cage rotor uses shorted bars for induction—no slip ring needed, unlike wound-rotor types.

2. How does slip ring vs. squirrel cage affect motor starting?

Slip ring allows resistance for high torque; squirrel cage relies on motor starter for current control.

3. Can I use a squirrel cage motor for air compressors?

Absolutely motors for air compressors thrive on their high starting torque and reliability.

4. What’s the role of circuit breakers in electric motors?

Circuit breaker types like electric breaker protect against overloads in AC motor circuits.

5. Is a 3-phase squirrel cage motor suitable for small applications?

Yes, motor small versions (under 1 HP) power tools and fans efficiently.

Technical References and Industry Standards

The concepts, formulas, design principles, and testing procedures detailed in this professional guide are derived from authoritative industrial standards and established electrical engineering texts. Key references include:

Official Standards and Guides

- NEMA Standard MG 1: Motors and Generators. (Used for NEMA Design Classes A, B, C, D, locked-rotor torque, and voltage unbalance derating factors).

- IEC 60034-30-1: International Standard for Efficiency Classes of Line Operated AC Motors (IE Code). (Used for IE1, IE2, IE3, and IE4 classifications).

- IEC 60034-1: Rotating electrical machines – Rating and performance. (Used for duty cycle, insulation classes, and general performance criteria).

- IEEE Std 112: IEEE Standard Test Procedure for Polyphase Induction Motors and Generators. (Used for defining motor testing, efficiency calculation methods, and parameter estimation).

- IEEE Std 43: IEEE Recommended Practice for Testing Insulation Resistance of Rotating Machinery. (Used for the troubleshooting section’s diagnostic requirements).

Core Textbooks

- Electric Machinery Fundamentals by Stephen J. Chapman. (A standard reference for the equivalent circuit, T-s relationship, and motor theory).

- Electrical Machines by P.S. Bimbhra. (Provides detailed analysis of construction, winding, and torque characteristics).